How to Preserve the Punjabi Language

The Punjabi language is in danger of extinction. Here’s what needs to be done about it.

This post is written by APF Research Fellow and Blog Writer Noah Usman, who graduated with a degree in linguistics from the University of California at Berkeley.

Punjabi is the official language of the Punjab province of Pakistan and serves as the native language of more than 30% of the country’s population. With over 70 million speakers in Pakistan spread across the largest province in the country, Punjabi is the most commonly spoken language other than Urdu and English. As an ethnic group, Punjabis form approximately half of Pakistan’s population and trace their heritage to a roughly defined geographical region in northern Pakistan and India, marked by the tributaries of the Indus River (the name Punjab comes from the Persian ‘panj’ (five), and ‘ab’ (waters), referring to these tributaries).

During the 1947 partition, the province of Punjab was split between India and Pakistan. Source

The geographical region of Punjab has historically been home to a heterogeneous population of Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, and Christian communities. Upon the partition of India in 1947, the newly independent states of India and Pakistan bore witness to a population displacement in which Muslims migrated from India to Pakistan, and Sikhs and Hindus vice versa. Today, Pakistani Punjab remains predominantly Muslim, while Sikhs constitute a slight majority in Indian Punjab.

The Punjabi language boasts an exceptionally rich history, originating from Sanskrit and incorporating a large number of loanwords from Persian and Arabic during the period of Mughal rule in India.

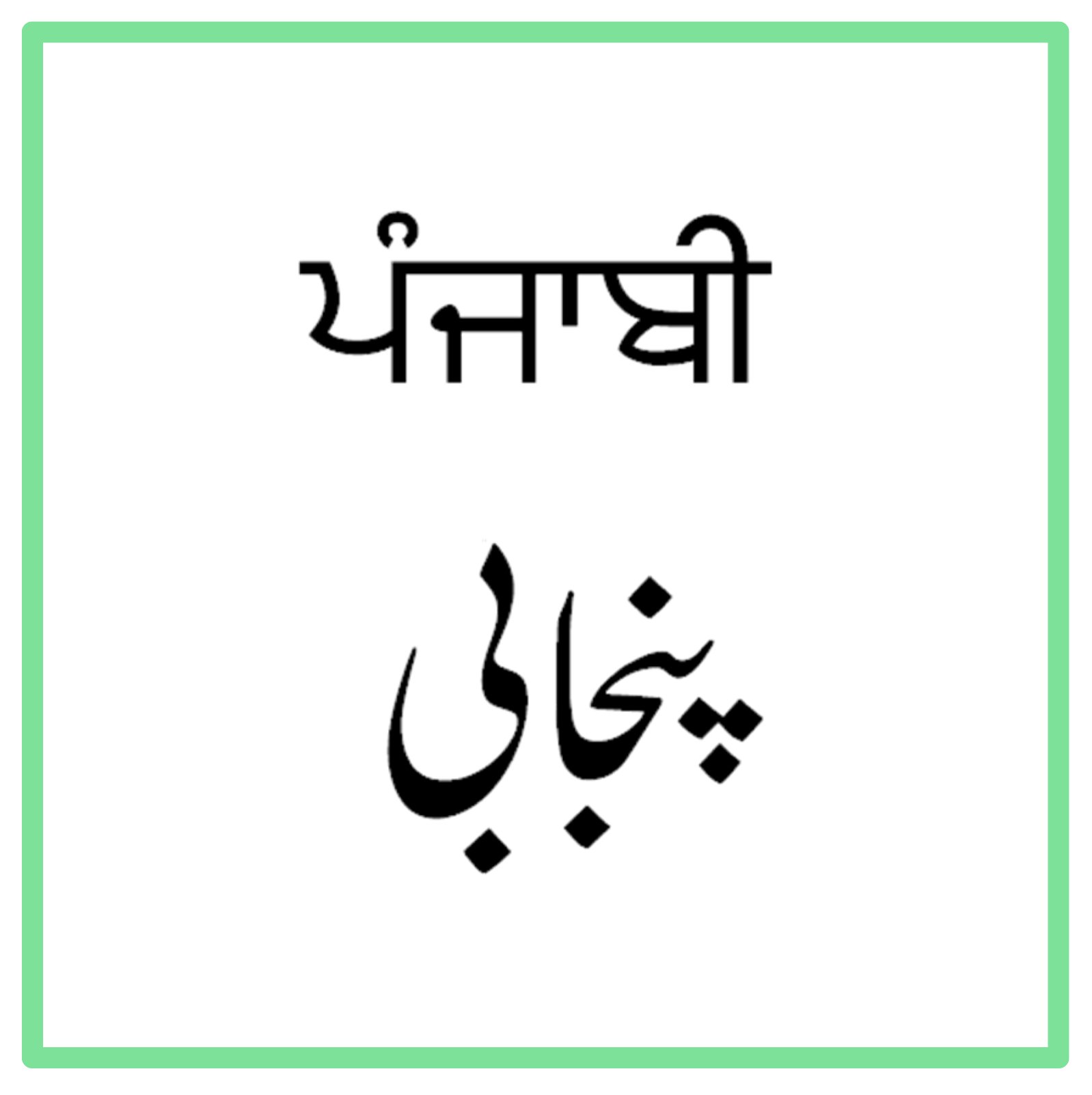

Punjabi also functions as the liturgical language of the Sikh religion due to its founders being indigenous to the region. Punjabi is currently written using two scripts: Shahmukhi (Perso-Arabic based) is utilized by Punjabi Muslims due to Arabic’s liturgical status in Islam; and Gurmukhi, a unique script predominantly utilized by Sikh and Hindu communities. These two writing systems hold official status in Pakistan and India, respectively.

Due to the sheer size of its speaker population and geographical territory, Punjabi shows some of the strongest instances of dialectical variation of any Pakistani language, with speakers often able to determine the city in which a person resides based on their pronunciation and word choice. Due to the magnitude of dialectical variation in Punjabi, linguists have not reached a consensus as to the total number of dialects, as this decision depends not only on the documented number of speakers of each dialect, but also on the speaker’s own ethnolinguistic identity. Most estimates of the total number of dialects range from 25 to 35, with the largest including Majhi Punjabi (spoken in the Lahore Metropolitan Area). Other commonly spoken dialects include the Shahpuri dialect (spoken in Faisalabad and the surrounding areas), and the Puadhi dialect (spoken in India’s Punjab province). The question of number of dialects is made even more interesting by the fact that many language varieties formerly considered to be dialects of Punjabi (including Potohari, Saraiki, and Hindko) are now considered separate languages by their respective communities.

The word Punjabi, written in Gurmukhi and Shahmukhi scripts.

Punjabi may not seem endangered at first glance; nevertheless, the language exhibits many of the strongest indicators of language endangerment. Language endangerment is measured through the Expanded Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale, which defines “definite endangerment” as the point at which “the child-bearing generation knows the language well enough to use it among themselves but none are transmitting it to their children.” While Punjabi has not yet reached this point in Pakistan society, intergenerational transmission continues to experience alarming decline, especially in the 21st century.

An overarching challenge is that Punjabi is subject to significant social stigma in urban areas where it faces a common stereotype as a mark of lower status and lack of education.

It is also commonly referred to as “crude,” due to how it sounds. The social stigmas associated with Punjabi are directly linked to its lack of significant presence in the educational system in Pakistan. Like most indigenous languages, Punjabi is largely omitted from institutional education in order to promote a policy of national-linguistic unity through Urdu and English, the country’s official languages.

Although not directly tied to any tangible factor, such perceptions often act as the single largest driving force behind language shift, already causing many Punjabi speakers to isolate use of Punjabi within the home with each other or with their servants, whom inevitably come from lesser developed and educated parts of the province and are more likely to speak only Punjabi. In some cases, families avoid passing the language on to their children altogether. This concern has been brought up periodically by the ‘Punjabi Parhao’ movement, an activist group lobbying for the inclusion of Punjabi as a core subject in primary schools in the Punjab province. Protests organized by the group include such disparate figures as academic language activists, media, and provincial and federal parliamentarians, alleging that the lack of mandatory Punjabi education in Pakistan constitutes a violation of the right to be educated in one’s native language.

While the Punjabi language maintains a relatively large speaker population, the fact that Punjabi is already experiencing abandonment in urban areas suggests that it may be primed for endangerment in as little as one generation. Lahore-based public health specialist Sana Aizaz, who served as a consultant for this piece, further explains that, as more areas of the Punjab province continue to develop, overall “knowledge is decreasing over time” of the Punjabi language, aided by the perception of Punjabi as “backward and traditional.” Endangerment has been addressed most commonly in the public space through political activism and government policy, specifically by lobbying for the inclusion of Punjabi in educational curricula, although this has not seen significant success.

Pakistani poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz wrote in both the Urdu and Punjabi languages.

For Punjabi to reverse the endangerment trends it faces, communities must confront the social stigmas associated with speaking the language. This can be done by increasing public knowledge about the language and its related culture, and teaching it at educational institutions. In terms of availability and content, the Punjabi language has a pluricentric body of literature, with notable authors hailing not only from Pakistan and India, but also from the diaspora in the United Kingdom and the United States.

Pakistani Punjabi literature mainly consists of politically oriented poetry and short stories, such as that from Faiz Ahmad Faiz (more commonly known for his Urdu writings) and Ali Arshad Mir. Both of these poets are known for their activism against economic inequality. Novels in the Punjabi language have also enjoyed substantial popularity, albeit often to a lesser extent. The main challenge here is that, with the exception of religious texts, Punjabi writings are rarely translated into Urdu and English, and are thus less likely to be taught in schools.

Notwithstanding the fact that Punjabis are the most populous ethnic group in Pakistan and speak its most common indigenous language, increased awareness of cultural contributions in Punjabi – ranging from literature to music and film – may help to increase perceptions of prestige in the Punjabi community, thus encouraging them to pass the language on to their children. This same trend would also benefit smaller indigenous-language communities which are themselves encroached upon by Punjabi in a multilayered pattern of language endangerment: the dominance of the official languages of Urdu and English reduces the prestige of provincial languages (including Punjabi), which in turn threaten already endangered languages in the same process.

While universal native-language primary education would certainly increase accessibility for native and monolingual speakers of indigenous languages, the reality that urban-centered businesses function almost exclusively through Urdu and English presents a significant challenge from a utilitarian perspective. However, in recognizing this state of affairs, we must also acknowledge that native-language education, while ideal for maintaining proficiency in a language, is not required for its survival. As documented by linguist Leanne Hinton in her biography collection Bringing Our Languages Home, “the most important locus of language revitalization is not in the schools, but rather the home,” as children spend significantly more time acquiring language in this environment.

This perspective is at once discouraging and liberating. While no amount of systemic change can simply revitalize a language for us, we ultimately hold the power as stewards of a language to decide its fate. The cultures and languages that our descendants will be exposed to may constitute a social trend, but they are nevertheless the result of a series of individual decisions.